RICHMOND:

database file source="h:/!Genuki/RecordTranscriptions/NRY/RichmondGuide.txt"

Robinson's Guide to Richmond (1833)

Part 2

The Castle

The Castle

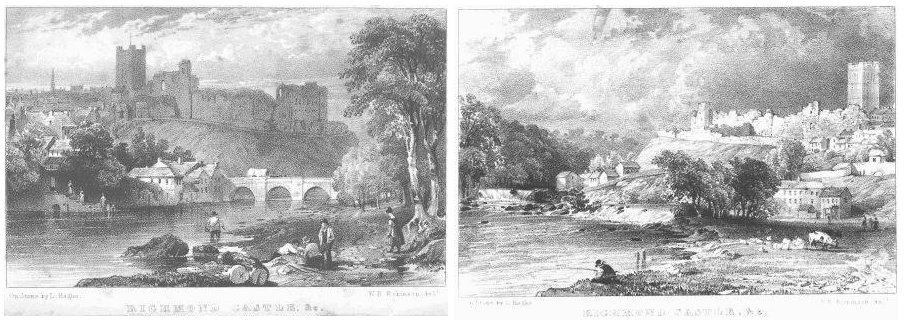

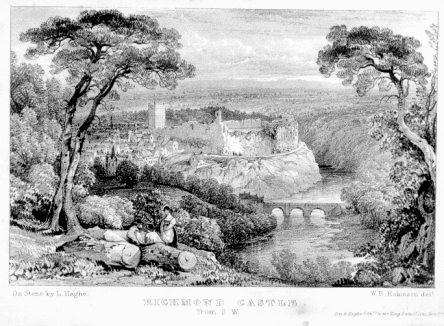

The first object which attracts the admiring gaze of the stranger

on approaching Richmond, is its noble Castle; once the abode of

a princely and powerful race, allied both by blood and subsequent

marriages to the royal family of England.

Its first foundation, as previously mentioned, was laid by

Alan the Red, the first Earl of Richmond, somewhere about the

year 1071. Dr. Whitaker contends, that as the Castle of Richmond

is not mentioned in Domesday Book, it could not have been commenced

until after the completion of that document in 1086.

He forgets, however, that the surveys, from which Domesday

was compiled, were made at different times, during several years

previous to its completion, and that the survey of this part of

the kingdom might, perhaps, be taken at a very early period of

the work. But again, we read in Domesday, (as cited by Coke 1,

Inst. 5 a) "Comes Alanus habet in suo Castellatu 200

maneria, et praeter castellariam habet 43 maneria;" -now

this clearly implies the existence of a castle some where or other

within the two hundred manors which composed the castlery

and as domesday does not mention any other castle within the district,

the castellatus may surely be presumed as referring to

the new erection at Richmond.

On approaching the ruin, we first enter an open space in front

of the Great Tower. This was termed the inner bailey, and was

surrounded by strong walls, some fragments of which remain: the

entrance was defended by two round towers, enclosing the massive

gate, before which was the drawbridge, crossing the deep moat

which encircled the town side of the castle. Passing through a

small door, we enter the area of the castle, and proceed to the

great square Tower, or Keep, which was erected in the year 1146,

by Conan, the third Earl of Richmond. This stupendous monument

of feudal quarrels, is ninety-nine feet high; its base at the

outside is fifty-four feet long, by forty-eight feet wide; and

the walls are no less than eleven feet in thickness. The lower

apartment is covered with a groined roof, resting on a strong

octagonal pillar; at the foot of which is a well, which supplied

the garrison with water. It had been constructed when the tower

was built, as part of the pillar is hollowed to accord with it.

This room was used as an arsenal to contain the military stores

of the fortress, and admitted no light from without, except through

the large arched door-way, which is supposed to have been the

entrance into the castle before this tower was built in

front of it. In one corner is a winding staircase, projecting

from the wall, leading up to the next story, which contains a

spacious apartment, lighted by three round headed Norman windows,

larger than are usual in such buildings; and also a small room,

or closet, at the corner, within the thickness of the wall. The

roof of this story has fallen in but from the next story the staircase

is carried within the wall to the top of the tower. There are,

also, various other recesses in the wall, lighted by loop-holes,

which, probably, served as sleeping rooms for the soldiers.

Passing along the eastern wall of the castle, we come to a

lesser Tower, in the, basement story of which is a small vaulted

Chapel, dedicated to St. Nicholas; its walls are lined with niches

for seats, and at the east end is a small window, in a spacious

recess, which contained the altar, with a closet on each side,

where the chalice, mass books, &c., might be deposited. The

rooms above were, perhaps, the apartments of the priest, who,

in those dark times, was a very necessary appendage to a nobleman's

establishment: not merely in his religious character, but as the

"clericus," the clerk or penman, he was frequently the

only person in the place who could boast of an intimate acquaintance

with the awful mysteries of reading, writing, and arithmetic,

and consequently was often in request to write letters, or acquittances,

and transact other temporal business for his lord.

Proceeding along the wall towards the south-east corner, we

reach some superior apartments; of the first, the only relic is

an elegant window, almost concealed in the clustering ivy, which

covers the outside of the wall, and adds much to its picturesque

beauty. The next is in a more perfect state:- the upper room has

been lighted by a tall window, looking into the area of the castle,

and has evidently been a private chapel, or oratory, as appears

by a small neat piscina, in the south wall; in the bottom of which

are two grooved holes for carrying away the sacramental wine,

when accidentally spoiled by any insect or other improper admixture.

Close to it is one of those singular relics of the Romish religion:

a confessional. It is an oblong loop-hole in the wall, neatly

constructed with large dressed stones; it is narrow on the inner

side, where the priest was seated, and opens wider into the next

room, where the person "doing his shrift," might unbosom

his failings without being seen by his ghostly adviser. How many

a dark story of rapine, of intrigue, and of blood, has been whispered

through this narrow cranny, where the winds now whistle unheeded

!*

*This chapel seems to have escaped the notice of all previous

Topographers.

Close to this interesting spot, is a Tower, commonly termed

the Gold-Tower, from the bottom of which is an arched passage,

leading, most probably, to some concealed vaults; but tradition,

which delights in the marvellous, asserts that it passes under

the bed of the river to the priory of St. Martin's!

In the extreme south-east angle, has been a well lighted and

(relatively speaking) comfortable room, which Norman gallantry

would, probably, appropriate to the ladies of the castle, as their

"bower," or private boudoir.

We now enter the great Hall of the castle; the scene long since,

of many a stately feast, and many a noisy carousal; it takes its

name from Scolland, lord of Bedale, and purveyor to earl Alan.

The five windows to the south, overlook the Swale and its opposite

banks; the principal entrance was by a flight of steps from the

court; and there are also the remains of a spiral staircase in

the north-west corner, which served for internal passage. The

lower apartment was, probably, used as a servants' hall, or dining

room for the common soldiers, &c. From hence was the entrance

to the cellar, and also a sally-port leading into the "cock

pit." Just at the end of the hall of Scolland, where the

wall breaks off even with the surface, is a seat which commands

a romantic view of the Swale. His late Majesty George the Fourth,

whose taste for the beauties of natural scenery was remarkably

vivid and correct, visited the spot whilst prince of Wales, and

expressed his high gratification by declaring it to be the noblest

prospect he had ever beheld.

Along the south wall of the castle were ranged the kitchen,

bakehouse, brewery, &c. and as this side of the castle was

impregnable to the modes of attack then in use, they offered no

obstructions to the defence, in case of a siege. In the south-west

corner, stands a solitary Tower, the lower part of which was the

dungeon, or place of confinement; it was entered from above, and

the wretched occupant would be almost entirely debarred the cheering

light of day, as there appears to have been no doorway or window

whatever to it.

Close by, is a large round headed arch, supposed to have been

the west window of the larger, or public chapel of the castle;

in which six monks, from Eggleston Abbey, were engaged by John

I. Earl of Richmond, to celebrate perpetual masses for the souls

of himself and his wife, &c. Of this chapel, there are no

other remains, except a postern under the window, intended probably

for the convenience of the monks.

To the east of the main wall of the castle, is an inclosed

space, called the Cockpit, which was also surrounded with a strong

wall, and included, on the north side, within the castle moat.

It seems, however, to have formed no part of the original structure,

and has, most probably, been afterwards taken in, to prevent any

hostile force from making a lodgement so nearly on a level with

the castle itself. It contained a garden for the use of the garrison,

and is now entirely cultivated as such. The castle has not been

the scene of any remarkable incident recorded in the page of history.

It stands, as it has stood for ages past, a silent ruin; Leland,

who went through the town between 1530 and 40, describes it as

"in mere ruin," and even so long ago as the fifteenth

year of Edward III. a judicial inquiry, made on the oaths of twelve

"good and lawful men," informs us with legal precision,

that the castle was considerably out of repair, and that "nihil

valet per annum," in plain English, it was "worth no-pounds

a year." It seems to have been first dismantled under an

order to that effect, made by King John, in the eighteenth year

of his reign, but was afterwards, partially inhabited by the various

retainers who claimed apartments by virtue of their offices.

It is now the property of His Grace the Duke of Richmond, who

derives his title from it, and in fact it is the only portion

of the extensive domains granted to the first Earls of Richmond,

which remains annexed to the title.

The broad and commodious Terrace Walk, round the base of the

castle, next demands attention: and it is here that the superiority

of the Yorkshire Richmond Hill over her Surrey namesake, is more

decidedly marked. The view from the latter present a monotonous

flat of quiet luxuriance; but here the eye is charmed with a rapid

succession of the most picturesque objects. The sloping banks,

covered with foliage of varied hues; the clear stream, murmuring

over its rocky bed, beneath the deep shadows of the trees which

line its banks, the towering battlements above, the precipitous

descent at our feet, the foaming cataract, and the placid pool;

and all these moulding into different combinations at the distance

of a few paces, form a series of views rarely equalled in so small

a compass.

IN the centre of the spacious Market-place, stands the TRINITY CHAPEL:

Data transcribed from:

Robinson's Guide to Richmond (1833)

Scan, OCR and html software by Colin Hinson.

This page is copyright. Do not copy any part of this page or website other than for personal

use or as given in the conditions of use.

Web-page generated by "DB2html" data-base extraction software ©Colin Hinson 2024